We are delighted to share Milton Moore’s review of our 25th Anniversary Season concert finale which featured eight extraordinary musicians performing works of Richard Strauss and Bartok, then concluded with the extraordinary Mendelssohn Octet.

Published May 2, 2016 By Milton Moore, The Day Staff Writer

Old Lyme — When folks look back on the many events and concerts of this 25th season of the Musical Masterworks series, it’s likely that the final performance in Sunday’s final concert of the year will be the first thing that comes to mind.

The chamber series’ artistic director and resident cellist Edward Arron wanted to go out with a bang, so he assembled seven other acclaimed string players for “an incredibly special piece to celebrate our 25th anniversary.”

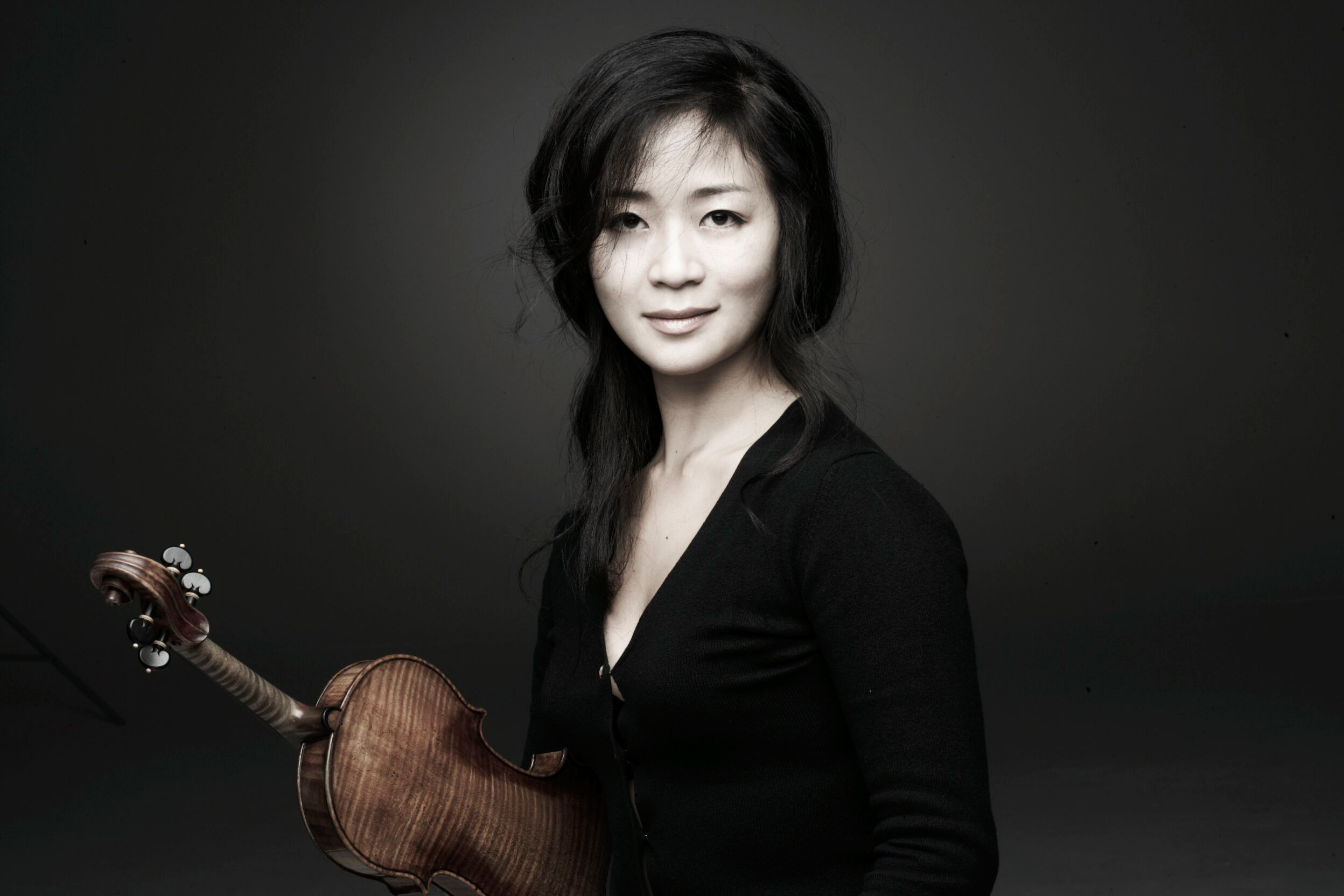

In that mix of assembled musicians were Masterworks stalwarts such as violinists Theodore Arm and Aaron Boyd, newcomers to the series such as founding member of the now-disbanded Tokyo String Quartet Kikuei Ikeda, and the violinist he introduced as “the fabulous Chee-Yun.”

The Korean violinist was one of the first stars to put the music series in the Old Lyme Congregational Church on the map, and she has remained a crowd favorite ever since. The celebratory piece programmed was that Beethoven’s Ninth of chamber music: the Mendelssohn Octet for Strings in E-flat Major. An exuberant tug of war between two string quartets, the octet explodes with teenage fervor and inventiveness (Mendelssohn was just 16 when he wrote it). It’s showy, intensely rhythmic and a perennial audience favorite.

Pairing Chee-Yun, in her first performance here in six years, and the octet, in only its second performance here, seemed a can’t miss, and from the start, with Chee-Yun standing front and center in her fiery red dress, leaning into the opening measures with a heavy bow and grab-the-spotlight attitude, it seemed that Arron made the right call.

The pair of weekend programs opened on a much more reflective note, with the under-performed and lovely string sextet prelude to Richard Strauss’s 1942 opera “Capriccio.” It was the last of Strauss’s 15 operas, and like his final songs, this sextet is calmer and more reflective than much of Strauss’s output.

The ensemble featuring Arron and Masterworks newcomer Wilhelmina Smith on cellos, Boyd and Arm on violins, and Che-Yen Chen and Dimitri Murrath on violas spun a charming unhurried weave of chromaticism, a tonal freefall through Strauss’s galaxy of melodic snippets that opened the program like the operatic prelude it is: A calm before the storm.

Arm and Ikeda then made a quick survey of seven of Bartók’s 44 Duos for Two Violins, written in the early 1930s as practice pieces inspired by Romanian, Serbian, Ukrainian, Arabic, and Hungarian folk tunes. Each is very short and tangy. From the wandering harmonies of “Szentivánéji” (“Midsummer Night Song”) to the rough and tumble earthiness of “Arab Dal” (“Arabian Dance”) and “Forgatós” (“Romanian Whirling Dance”), the violinists left us wanting more.

The ensemble reshuffled to perform three sections of Sicilian composer Giovanni Sollima’s long, minimalist Viaggio in Italia for String Quintet written in 2000. In the three sections performed, violinist Boyd and violist Murrath were in the forefront – except for post-modern moments such as when Smith played her cello body with two hands like a conga drum. The second section, a long and haunting arioso called “Zobeide,” was hauntingly luminous, with that hypnotic pulse and harmonic progression we associate with Philip Glass and with Boyd punctuating the pulse with sinuous, long glissandos.

The second half was all oc- tet, though Chee-Yun’s ability to turn up the volume of her Strad made it seem more like a concerto for violin and string orchestra. The groupings of Arm, Chen and Boyd standing on one side and Chee-Yun, Ikeda and Murrath on the other made the interplay vivid, as Mendelssohn split his players for visual effect, as well as scoring. When Arm’s group all leaned into unison pizzicatos, the effect felt like a big band dipping and weaving in unison. It was great, if unintended, stagecraft.

The third movement scherzo is one of the singular moments of inspiration (ah, youth!), predictive of the “fairie music” from Mendelsohn’s incidental music to “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” and other scampering allegrettos to follow. The score says it should be played as fast and as quietly as possible, and the Masterworks ensemble took that pacing to heart, tossing around the cascading eight-note figures from musicians to musicians like firecrackers with burning fuses. The blistering phrases by the paired cellists were thrilling stuff indeed.

Then came the finale, with the tempo still a runaway train and Chee-Yun stepping up and taking over sonically. Was it too fast? Was it too aggressive? Was it just too much? Well, no one will forget it. And that’s probably exactly what Arron had in mind.